By Veronica Li

I’ve heard about Chinese “coolies” building the railroad across America. But as a 1960s immigrant from the big city of Hong Kong, I thought I had nothing in common with these villagers who came to the “Gold Mountain” 150 years ago. However, the recent hostility against Asian Americans following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has awakened my interest in how this history has shaped my time in the U.S. It became common to hear someone yell at us, “Go back to where you came from.” Perpetrators attacked Asians of all nationalities, as well as robbing and vandalizing our stores and institutions.

This violence has inspired me to delve into Chinese American history. I feel this knowledge is key to discovering my place in this country. That was why I joined the two-day Gold Mountain Tour in the fall of 2023. Standing on top of the Sierra Nevada’s Donner Summit, where Chinese railroad workers completed a marvel of 19th-century engineering, I’d never been so proud to be Chinese American. Without these workers, the Transcontinental Railroad linking “sea to shining sea” wouldn’t have been possible at this critical juncture of American history.

To the nascent American empire, the railroad was the bond to secure the fragile union. The tour was sponsored by the 1882 Foundation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. John Kusano, the organizer of the tour, is a director of the 1882 Foundation and has served 35 years with the Forest Service. The docent, Phillip Sexton, is a historian, a former Forest Service member, and a contributor to the seminal book on the subject, The Ghosts of Gold Mountain by Gordon Chang of Stanford University.

These volunteer guides ran the tour without a hitch, showed us the spectacular views of the Sierra Nevada, and told the story of the first Chinese Americans.

The story begins in 1862, when President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act, authorizing the construction of a Transcontinental Railroad to connect the country east to west. This was at a time when the civil war threatened to tear apart the north and south. The enterprise would be a public-private collaboration.

The government would provide bonds and land grants to two private companies. The one in the West, called Central Pacific Railroad (CPR), would be responsible for the road starting from Sacramento, California, while the one in the East, Union Pacific (UP), would start from Omaha, Nebraska. Seven years later, the two tracks connected in Utah to form the Transcontinental Railroad.

Shortly after CPR broke ground in 1863, they realized the difficulty of getting laborers. The company initially wanted to hire only White men, but only a few hundred responded to the recruitment efforts and many didn’t stay long, preferring to find their fortune in gold and silver mining. Railroad work was hard and paid little.

One of the company directors, Charles Crocker, suggested hiring Chinese workers. They had come for the gold rush in the 1850s, but a decade later, the easy gold was gone, and discriminatory actions by both the government and public had driven many Chinese from the goldfields. Crocker had recruited a Chinese crew for road construction earlier and had been satisfied with their performance. However, James Harvey Strobridge, the construction supervisor under Crocker, objected. He thought the Chinese were too small and weak to do the heavy labor. His boss’s legendary reply was, “Did they not build the Chinese wall, the biggest piece of masonry in the world?”

By Veronica Li. Bloomer Cut

The first stop of our tour was Bloomer Cut. All 56 of us disembarked from the comfortable coach and walked ten minutes to the railroad tracks. To my untutored eyes, it was just a railroad curving through a cut in a hill. Fortunately, Phil, the docent, taught me the significance of this site.

This was where the first experimental group of about twenty Chinese joined the White workforce. There they faced a long, tall ridge made of a conglomerate rock as hard as concrete. Before power tools, the picks and shovels at the workers’ disposal were no match for the rock. Black powder had to be used to blast open a 63-foot deep, 800-foot-long cut at the center of the ridge. An accidental explosion killed one worker and blinded Strobridge in one eye, bringing home the danger of these volatile explosives.

From then on, his Chinese workers called him “One-eyed bossy man.” Strobridge had this to say of them: “They learn quickly, do not fight, and are very cleanly in their habits.”

As the Chinese mastered drilling, blasting, and other railroad work, the company was so impressed that they recruited workers from southern China. Altogether, 12,000 to 15,000 had worked on the railroad, making up 90 percent of CPR’s workforce.

Our second stop was the Cape Horn Promontory, overlooking a gorge surrounded by mountains covered with trees and shrubs. The place was nicknamed after the notoriously treacherous Cape Horn near the tip of

South America. Sculpting a path along the sheer cliffs was a major test for the Chinese workers. To create a ledge for the railroad bed, they were lowered by rope onto the cliff to drill holes and plant explosives in the rocks. Once they lit the fuse, they hollered to be hauled up. But sometimes the powder exploded before they reached safety, and there were a number of casualties. Images of the period show the use of wicker baskets to lower workers onto the mountainside, but modern research indicates the baskets weren’t employed at Cape Horn.

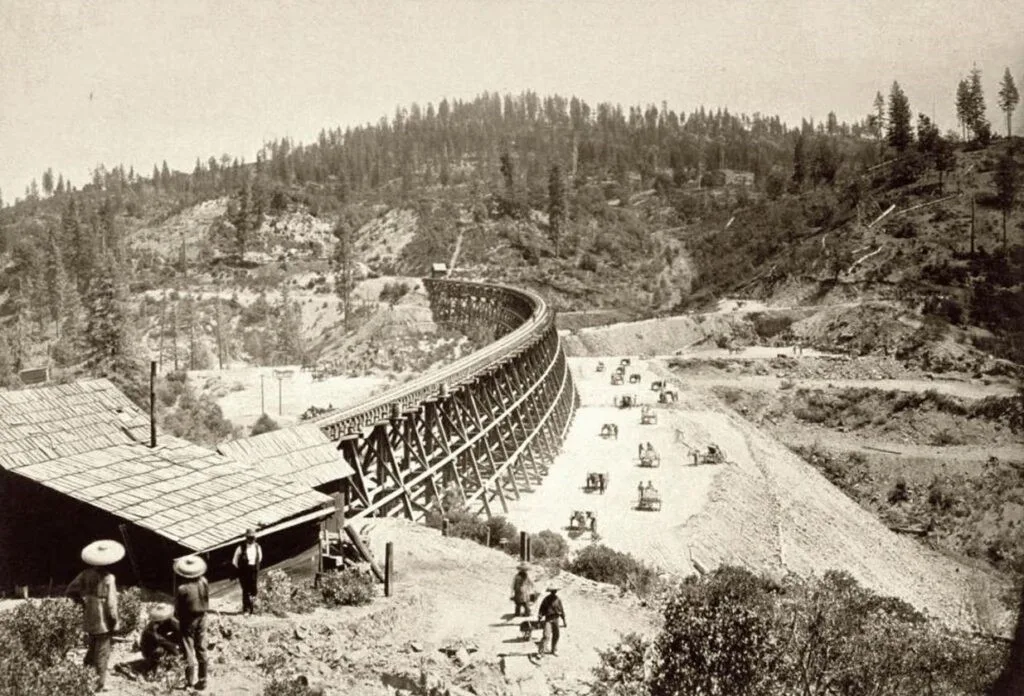

Regardless of the method used, building a passageway in seemingly insurmountable conditions was a tremendous achievement. From the mountain, we arrived at a ravine near Secret Town. (Miners wanted to keep the place secret after discovering gold there.) The tracks here looked ordinary until Phil told us what was buried underneath. It was a trestle bridge, a magnificent centipede-like structure built with locally felled trees.

At 1,110 feet long, 95 feet high, and stacked like a house of cards, it must have been a frightening sight for passengers looking down into the deep ravine. Because the wood often caught fire from embers from the train’s smokestacks, Chinese workers were assigned to shore it up with dirt. The ravine is now completely filled, which is why we can no longer see the remarkable structure.

Secret Town Trestle

Summit Tunnel was the highlight. Before the tour, John, the organizer, had sent us several emails to prepare us: Bring layered clothing as rain and temperatures in the forties are in the forecast. Also, bring walking sticks for the hour-long hike to Summit Camp. As the drizzle turned into sleet, I regretted not wearing my long johns. And as the terrain became more and more rugged, I regretted not bringing my walking sticks. In

hindsight, the “hardships” gave me a taste of the harsh conditions at 7,000 feet elevation in the Sierra Nevada.

Summit Camp, where several hundred Chinese workers lived for two years, 1865-67, is a barren landscape of granite outcroppings and slippery gravel. In relatively flat areas, remnants of the foundations of huts remain.

Already shivering on a fall day, I can’t imagine living in a flimsy shack in freezing temperatures and heavy snow. In the winter of 1866-67, numerous storms dumped record snow here. Imagine opening the door in the morning to find a white wall blocking your way. To get to work, you have to tunnel through the snow.

You live in this maze of sunless burrows for months until the snow melts. But that’s not the worst. An avalanche can wipe you and your companions away in the middle of the night. Such incidents happened.

Some of the bodies were found in the spring. One of them, who was swept away while he was working, was found still clutching his shovel.

If living conditions were bad, working conditions were insufferable. For the railroad to cross the Sierra Nevada, digging 15 tunnels through solid granite was required. Three-man teams hacked away at the face of the mountain. While one held the iron chisel, two others took turns to pound the chisel with a sledgehammer.

How many hands were smashed is unknown. When a two-foot hole was dug, explosives were planted, and the men would run for their lives after lighting the fuse. Around 2,000 workers were killed in the construction of the railroad from Sacramento to Omaha.

Summit Tunnels

Progress was an excruciating average of 14 inches a day, which increased to 22 inches when nitroglycerin was introduced. Workers operated in three shifts, 24-7, digging into the mountain from two ends. At this rate, it would take them five years to complete the longest tunnel, called #6. Engineers came up with a plan. They measured the point that would be the center of the tunnel and ordered the workers to dig a vertical shaft to a depth of 75 feet.

From the center, they would dig outwards to meet those digging inwards, thus doubling the number of facings from two to four. In this way, the 1,687-foot summit tunnel was completed in two years. These original tunnels are no longer in use as the railroad has been rerouted. Union Pacific, the current owner, has closed the tunnels to tourists. Unfortunately, trespassers have smeared the walls with graffiti, a

grave disrespect to the workers who shed sweat and blood building them.

The 1882 Foundation is now working with other concerned agencies to declare the area a National Historic Landmark. They are working with UP to support access to the tunnels in order to expand their educational programs and tours.

I had the chance to peek into the short tunnel #7. In spite of the graffiti marring the walls, the deep holes bored into the granite and blast scars are still visible. Perhaps on future Gold Mountain tours, visitors would be able to inspect the wonders of tunnel #6.

Another spectacle on the summit is the Chinese Wall. It’s a 75-foot-high retaining wall to hold the fill for the gap between tunnels #7 and #8. Stones excavated from the tunnels were chiseled into blocks of varying sizes and stacked together without mortar. Today the wall stands in all its glory after all these years and countless trains running over it. Only the best masonry skills can attain such endurance.

Finally, back in the comfort of the warm bus, I looked out once more at the summit. The Chinese workers’ ingenuity, talents, industriousness, and fortitude are written all over the mountains. But what impressed me more than anything else was that they dared to stand up for themselves, contrary to the popular belief that they were “coolies” and therefore slaves. They went on strike to demand higher pay and shorter shifts in the life-threatening tunnels. Their wage of $30 a month, minus the board they had to pay out of their own pockets, was grossly unequal to white workers’ remuneration. CPR countered by cutting off all supplies to the strikers. After starving for eight days, they succumbed. But they had made their statement. Company managers realized they could no longer take the Chinese workers for granted. There is evidence CPR conceded to the workers’ demands shortly after.

The last leg of our journey was a train ride from Reno back to where we started, Sacramento. Watching the scenic view of mountains, forests, and rivers, I thought of the thousands of Chinese workers who made myride possible. They paved the way not only for the railroad but also for me as a Chinese American. They’re my roots and I continue in their footsteps in pursuing the American dream of liberty, opportunity, and happiness.

This was the same quest that motivated the first European settlers in the New World. So now I know, we all come from the same place.

Note: This Gold Mountain Tour is the fifth such tour. There is one every year (except during the height of COVID). Anyone interested should contact the 1882 Foundation.