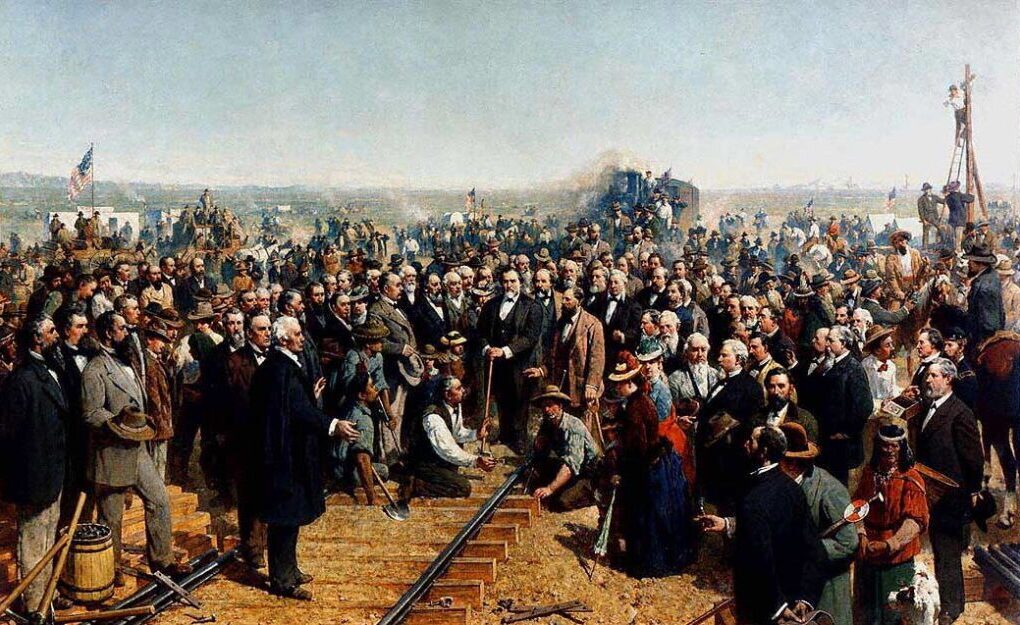

2024 Golden Spike Celebration – May 11, 2024

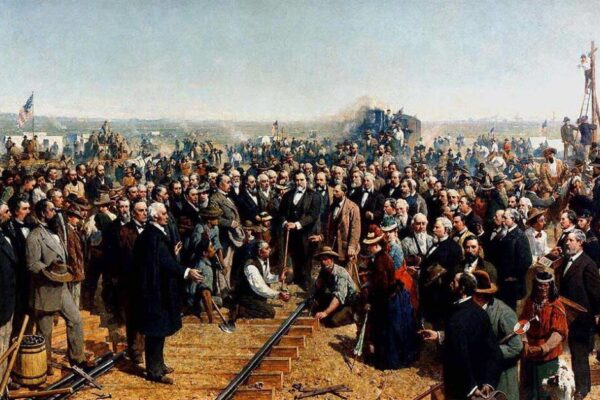

The “Golden Spike” is a significant symbol in American history, particularly associated…

The “Golden Spike” is a significant symbol in American history, particularly associated with the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad…

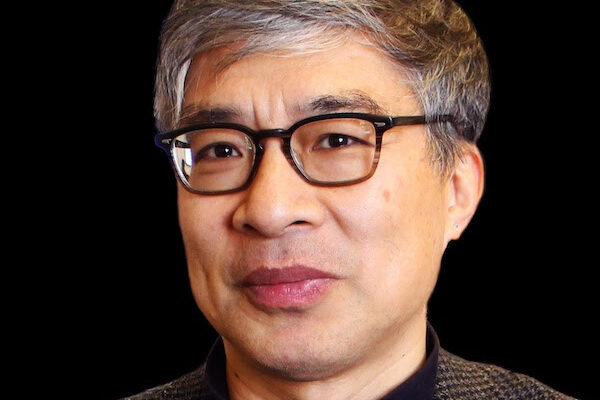

Speaker: Guobin Yang 12 p.m. Central | Thursday, May 2, 2024 In the mid-1990s, private internet firms spearheaded the…

14 senior year students from 12 high schools or home school in twin cities were selected to receive 2023-2024 CAAM…

Light of Chinese Culture Performance Series Fridley High School Auditorium 6000 W Moore Lake Drive, Fridley, MN 55432 3:00 PM…

From May 4-26, 2024, History Theatre and Theater Mu’s world premiere Blended 和 (Harmony): The Kim Loo Sisters will shine…

Following the unreasonable interrogation and denial of entry at Washington International Airport, leading to the deportation of several Chinese students,…

YOU’RE INVITED! Join us for CAMOC’s 23rd Benefit Gala Dinner Saturday, May 18th, 2024 at New Furama Restaurant More details: https://ccamuseum.org/

2024 Chinese American Convention “Chinese American Convention,” organized by United Chinese Americans (UCA), is the largest national get-together event, the…

California’s Ron and Lloyd Dong brothers donated $5 million in ancestral property to San Diego State University’s Black Resource Center…

College of Liberal Art 2nd Floor Hallway with exhibits on display By Greg Hugh Poetic Visions, an exhibit featuring selections…

4:00 PM | Thursday, April 25, 2024 McNamara Alumni Center Under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, China has increased its defense spending,…

Annual Data on Minnesota Manufactured Exports – Published in March 2024 For More Information: Mary Haugen ([email protected]) Minnesota exported about…